Historical Background

The Luxor Temple stands as one of ancient Egypt’s most impressive and symbolically rich temple complexes. Its origins lie in the New Kingdom era (circa 1550 – 1070 BCE), a time of Egyptian political and religious flourishing. The name Ipet-resyt means “Southern Sanctuary”, reflecting its position in the southern capital region of Thebes (modern Luxor) and its complementary role to the neighbouring temple complex of Karnak Temple Complex.

Although no single pharaoh built the temple in its entirety, key contributions came from several rulers. The earliest extant shrine is attributed to Hatshepsut of the 18th Dynasty (c. 1473-1458 BCE) — a rare early surviving element within the complex. The major core structure, including the peristyle court and colonnade, was erected by Amenhotep III (c. 1390-1352 BCE) of the same dynasty. Later, during the 19th Dynasty, Ramesses II (c. 1279-1213 BCE) carried out extensive additions, including the grand pylon entrance, statues and obelisk.

The temple did not remain static: during the Roman period (third century CE) it was adapted—for example, a chapel of the goddess Mut was converted into a Tetrarchy cult chapel, then later into a Christian church. In later centuries, a mosque — the Abu el‑Haggag Mosque — was built on the site, illustrating the layered and continuous use of the site through multiple epochs.

In 1979, Luxor Temple, together with the remains of ancient Thebes and its necropolis, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

2. Location and Urban Context

Located in the heart of modern Luxor, on the east bank of the Nile, the temple is part of what ancient Egyptians regarded as their capital city of Thebes. The east bank was reserved for living and cultic functions, whereas the west bank was the realm of the dead (necropolis). The temple lies around three kilometres south of Karnak Temple and was originally connected to it by a processional avenue flanked by sphinx statues, sometimes called the “Avenue of the Sphinxes.”

Unlike many temples aligned along an east-west axis, Luxor Temple is oriented slightly differently — aligned toward Karnak, reflecting its participation in the annual festival of Opet (see below).

Because of its central location within the city of Luxor, the temple remains visually prominent and accessible, even beyond its archaeological significance. It forms a dramatic backdrop as one walks along the Nile corniche at dusk or evening.

3. Architectural Layout and Key Features

The architecture of the temple reflects the religious ideology and ceremonial purpose of the complex. As one progresses from the entrance inward, there is a ritual path from the outer world to the sanctified core, moving through successive spaces of increasing sacredness.

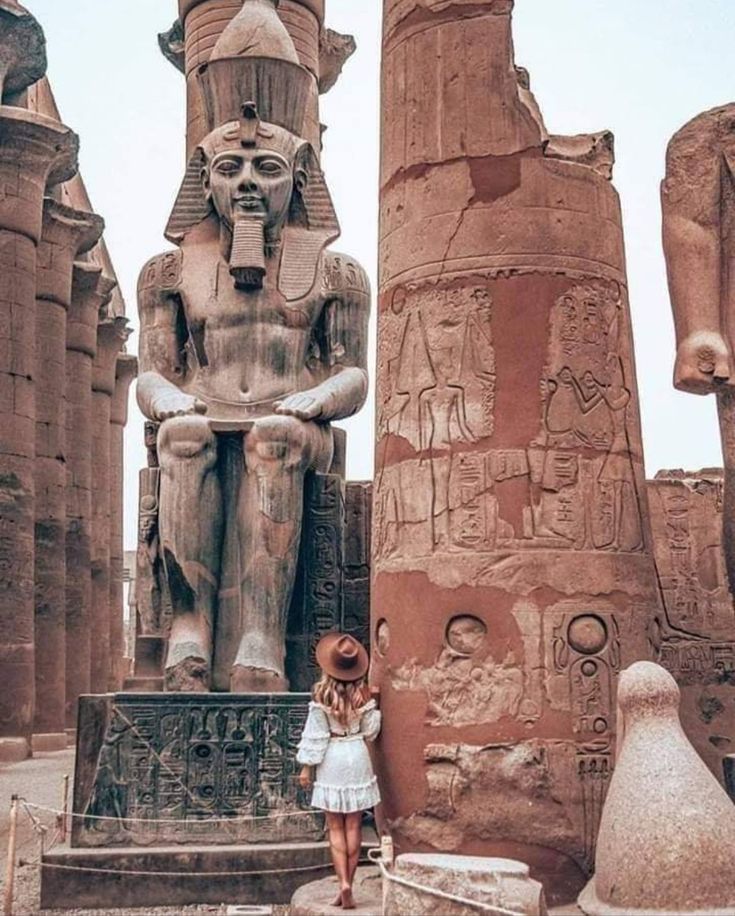

3.1 Entrance and Pylon of Ramesses II

The most imposing first element for visitors is the massive pylon built under Ramesses II. The pylon front measures roughly 65 m wide and is decorated with reliefs that depict the pharaoh’s military campaigns, most notably his victory over the Hittites and the famed Poem of Pentaur. Flanking the entrance are colossal seated statues of Ramesses II (one of a pair), and, previously, two obelisks stood before the pylon — one remains in situ, the other was gifted to France and now stands at the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

3.2 Great Open Courtyard (“Court of Ramesses II”)

Beyond the pylon lies an open peristyle court, built by Ramesses II, surrounded on three sides by a double row of papyrus-bundle‐style columns. Within this court are further statues of the king, lending a monumental scale to the space. One extraordinary aspect is that the existing mosque structure (Abu el-Haggag) stands atop some of the columns on the northeast side, illustrating the multi-layered history of the site.

3.3 Colonnade of Amenhotep III

Proceeding inward, one encounters the magnificent colonnade built by Amenhotep III: fourteen papyrus‐cluster columns each around 19 m high, arranged in two rows. These columns stand as a visual and spiritual transition zone between the outer court and the inner sanctuaries. The walls flanking the colonnade depict scenes of the Opet Festival, royal birth narratives and other ritual themes.

3.4 Hypostyle Hall and Inner Chambers

Behind the colonnade is a hypostyle hall lined with 32 large columns. Beyond these halls lie a series of interconnected rooms culminating in the sanctuary of the sacred barque (the ritual boat of the god). The rooms also feature the so-called Divine Birth reliefs, which depict Amenhotep III’s divine origin through the god Amun, symbolically validating his kingship.

3.5 Materials, Orientation and Symbolism

The temple is built primarily of sandstone, likely quarried in Nubia, and the reliefs and statues display high craftsmanship. Architecturally, the straight axial plan (entrance → court → colonnade → sanctuary) reflects ritual movement and hierarchy of sacred space. Some Egyptologists interpret the layout symbolically as representing the human body (feet → legs → torso → head) or the king’s journey from mortal to divine.

The alignment toward Karnak rather than strictly east-west underscores its function within the Theban religious landscape — it was specifically involved in the festival when the cult gods of Thebes moved from Karnak to Luxor for a time.

4. Religious and Ceremonial Function

What makes Luxor Temple especially significant is its role not simply as a cult temple for a specific god, but as a centre for the idea of kingship itself and the renewal of royal power.

4.1 Cult of the Theban Triad & Royal Cult

Though the Theban triad of Amun (or Amun-Ra), his consort Mut and their son Khonsu were central deities in Thebes, Luxor Temple appears to emphasize the pharaoh’s divine role. Many scholars argue that the temple was dedicated to the rejuvenation of kingship more than to a specific god.

During rituals, the king was symbolically reborn each year, reaffirming his role as an intermediary between gods and people. The Divine Birth reliefs reinforce this by presenting the king as the son of Amun.

4.2 The Opet Festival

One of the most important rituals associated with the temple was the annual Opet Festival. During this festival, the cult statues of Amun, Mut and Khonsu were transported from their main temple at Karnak along the Avenue of the Sphinxes to Luxor Temple. There they stayed for several days, renewing the king’s power, before returning.

Because of this role, the temple’s orientation and layout fit into the wider Theban sacred geography and annual ritual calendar. The processional axis reinforced the connection between king, cult and city.

4.3 Later Religious Adaptations

Over the centuries, as the political and religious landscape of Egypt changed, the temple adapted: in the Roman period a Tetrarchy chapel was installed; in Christian times parts were used as a church; later a mosque (Abu-el-Haggag) was built on the site; even today the mosque is in use during the annual festival of Abd al-Haggag, showing a remarkable continuity of sacred space.

5. Restoration, Preservation and Excavation

Given its long use and exposure to the elements, Luxor Temple has undergone significant restoration and archaeological work.

In modern times, efforts by the Egyptian government’s monuments authorities (such as the Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities) have focused on stabilizing the sandstone structure, documenting reliefs, and managing visitor impact.

Archaeologists have also been excavating the processional avenue of sphinxes that once linked Luxor with Karnak and restoring that once-grand access route.

Challenges include erosion, rising water tables, pollution, and the balancing of tourism with preservation of original surfaces. The presence of the mosque inside the court, while culturally significant, has also entailed structural pressure and required sensitive handling.

6. Visitor Experience and Significance Today

For a visitor today, Luxor Temple offers both a dramatic aesthetic experience and a deep immersion into ancient Egyptian culture.

-

The dimly-lit hypostyle hall and long colonnade give a powerful sense of scale and time.

-

At dusk, lighting accentuates the relief-carved walls, making the site particularly atmospheric.

-

Because it sits within the modern city, it is easier to visit than many of the remote tombs on the west bank, and remains open into the evening hours.

-

One of the most memorable views is of the obelisk, seated statues of Ramesses II and the pylon façade, juxtaposed with the bustling city of Luxor and the Nile nearby.

From a cultural-heritage perspective, Luxor Temple remains a living monument: a temple complex that has been used continuously (in varying forms) for thousands of years. This continuity connects ancient Egypt to the present in a tangible way.

7. Significance and Legacy

Luxor Temple stands out for multiple reasons:

-

Royal Ideology: Unlike many Egyptian temples dedicated primarily to a god, Luxor’s central focus is the pharaoh’s divine nature and the renewal of kingship.

-

Ceremonial architecture: The straight, visually powerful axis of the temple, its colonnades, courts and sanctuaries, all serve ritual movement and dramatic visual progression.

-

Urban integration: Its location within the everyday city of Luxor (ancient Thebes) shows how the sacred and civic spheres interlinked.

-

Continuity of use: From pharaonic temple to Christian church to Islamic mosque, the site reveals layers of religious history and continuous human use.

-

Tourist and heritage value: Today, it remains an essential part of Egypt’s cultural tourism, a “must-see” site for those exploring the Theban region, and a symbol of ancient Egyptian grandeur and resilience.

8. Challenges and Preservation Concerns

Despite its importance, Luxor Temple faces a number of modern challenges:

-

Environmental stress: Sandstone erosion, urban pollution, rising groundwater and Nile flooding all threaten the site’s integrity.

-

Tourism pressure: Large numbers of visitors, lighting installations for evening visits, and modern infrastructure can strain the ancient fabric.

-

Urban encroachment: Being within a modern city means constant balancing between preservation and development.

-

Interpretation and authenticity: Restoration efforts must carefully manage accurate historical reconstruction without over-restoring or falsifying ancient surfaces.

-

Cultural layering: The presence of the mosque and modern city life can complicate archaeological access, but also make the site a living heritage rather than a pure “ruin”.

9. Conclusion

The Luxor Temple is far more than a spectacular set of ruins. It is a living monument to the spiritual, political and cultural life of ancient Egypt — the stage for royal ideology, great festivals, and the interplay of god, king and people. Through its architecture, reliefs, and enduring presence in the heart of Luxor, it continues to tell a story that spans more than three millennia.

Whether one approaches its grand pylon at dusk, walks the stone-paved axis from courtyard to sanctuary, or considers the long procession of kings who built, modified and worshipped within its walls, the Luxor Temple invites reflection on the power of belief, the permanence of architecture, and the ways in which the ancient and modern worlds intertwine.

Ready to explore Luxor Temple? Check out our exclusive Egypt Tour Packages and start planning your journey today!