Introduction

In the golden sands of Egypt’s timeless desert, where history whispers through stone and wind, stand two monuments tied to one of the greatest rulers of the Middle Kingdom: the Pyramids of Amenemhet III. Unlike the familiar grandeur of the Giza pyramids, the works of Amenemhat III represent a different chapter of Egypt’s architectural journey — one that blends ambition, experimentation, and endurance.

For modern travelers, visiting these pyramids is more than just gazing at ancient stonework; it is stepping into the world of a pharaoh whose reign marked both prosperity and challenges. Whether you are an archaeology enthusiast, a history lover, or a curious tourist, the story of Amenemhat III’s pyramids at Dahshur and Hawara offers a journey into a side of Egypt that is often overlooked, yet deeply fascinating.

Who Was King Amenemhat III?

Amenemhat III, the sixth pharaoh of Egypt’s Twelfth Dynasty, ruled during the Middle Kingdom, roughly from 1860 to 1814 BCE. His reign was long and prosperous, lasting over four decades, and he is often regarded as one of the most capable rulers of his era.

Unlike earlier pharaohs who concentrated solely on military expansion or temple building, Amenemhat III balanced his rule with economic development, infrastructure, and cultural patronage. His administration oversaw:

-

Massive irrigation projects that controlled flooding of the Nile.

-

Expansion of trade routes with Nubia and the Levant.

-

Quarrying of stone from distant deserts to fuel temple and pyramid construction.

-

The flowering of arts, sculpture, and religious innovations.

His vision of power and divine kingship was not just expressed through governance but also through architecture. To immortalize his legacy, Amenemhat III built two pyramids: one at Dahshur (often called the “Black Pyramid”) and another at Hawara, which became his final resting place.

The Black Pyramid of Dahshur

Location and Background

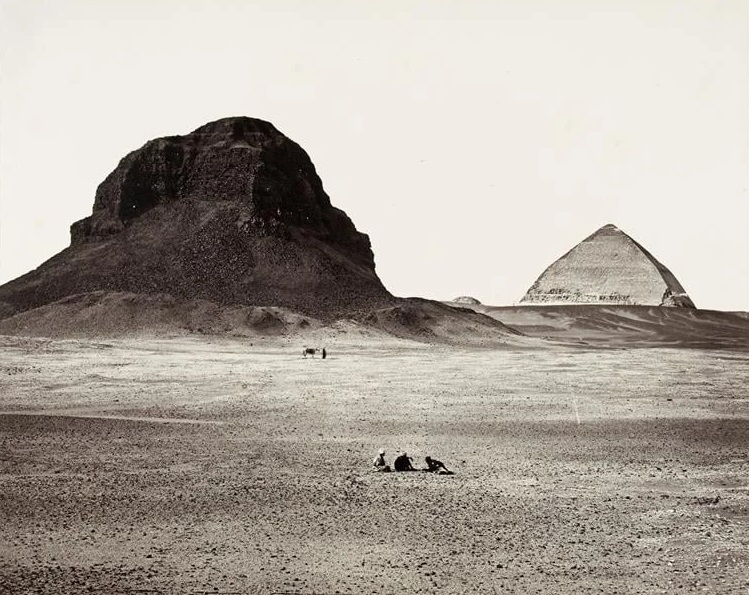

The first pyramid of Amenemhat III was constructed at Dahshur, about 40 kilometers south of Cairo, an area already rich with royal monuments from earlier dynasties. The site was chosen strategically, near the Bent and Red Pyramids of Sneferu, connecting Amenemhat’s reign with the Old Kingdom’s legacy.

This structure came to be known as the Black Pyramid because of its dark, decayed mudbrick core that became visible when its limestone casing eroded away. Unlike the shining white pyramids tourists usually imagine, the Black Pyramid looks hauntingly ruined today, yet it holds secrets that make it unique among Egyptian monuments.

Architectural Innovation

The Black Pyramid was not built entirely from stone, as many earlier pyramids had been. Instead, its core consisted of mudbrick, reinforced with limestone casing. This experimental approach was ambitious but flawed. The heavy weight caused cracks, and water seepage from the nearby Nile weakened the structure over time.

What makes the pyramid particularly fascinating is its complex internal design. It contained:

-

A labyrinth of corridors and chambers.

-

Burial apartments not only for the king but also for royal women.

-

A sophisticated arrangement of security features to deter tomb robbers.

Archaeologists uncovered the remains of royal burials, jewelry, and funerary goods within the pyramid, offering rare insight into Middle Kingdom burial practices.

Symbolism

Even though structural problems plagued the pyramid, its construction symbolized Amenemhat III’s ambition. The attempt to push the boundaries of engineering reflects a pharaoh determined to innovate rather than merely replicate the past. The Black Pyramid may not have endured perfectly, but it stands as a testament to bold experimentation in Egyptian architecture.

The Pyramid of Hawara

Why a Second Pyramid?

Due to the instability of the Black Pyramid, Amenemhat III commissioned a second pyramid at Hawara, located near the Faiyum Oasis. This was not unusual; several pharaohs of earlier dynasties built multiple burial monuments. However, for Amenemhat III, the Hawara Pyramid served as his true tomb.

Structure and Features

The Hawara Pyramid appears modest at first glance — a mound of stone that has lost much of its outer casing. Yet, beneath its surface lies one of the most fascinating constructions of the ancient world: the Labyrinth of Hawara.

The Labyrinth was a vast mortuary temple attached to the pyramid, described by ancient Greek historians such as Herodotus and Strabo. They marveled at its countless halls, courtyards, and chambers, claiming it rivaled the pyramids of Giza in wonder. Sadly, much of it has been lost, but archaeological excavations confirm that it was indeed a massive and complex structure.

The pyramid itself was built using a core of mudbrick with limestone casing, similar to Dahshur’s design but improved in stability. Inside, it held a network of passages and a quartzite burial chamber designed to resist looting. Despite these measures, ancient robbers still managed to break in.

Discoveries

In the 19th century, archaeologist Flinders Petrie excavated the Hawara site and uncovered extraordinary finds, including the famous Faiyum Mummy Portraits — stunning painted images attached to Roman-era burials discovered nearby. These portraits are not directly from Amenemhat’s time but illustrate how the site remained sacred and reused for centuries.

.jpg)

Amenemhat III’s Legacy Through His Pyramids

The dual pyramids of Amenemhat III highlight several aspects of his reign:

-

Innovation and Experimentation – His willingness to try new materials and techniques, even at great risk.

-

Religious and Political Symbolism – By linking his monuments to Dahshur and Hawara, he tied himself to both the Old Kingdom legacy and the thriving Faiyum region.

-

Economic Power – The sheer scale of his building projects reflects Egypt’s wealth during his reign.

-

Human Ambition – These pyramids embody the eternal quest for immortality, even in the face of natural limitations.

For tourists, this legacy makes visiting his pyramids a journey into the mind of a ruler who dared to dream differently.

Visiting the Pyramids Today

Dahshur: The Black Pyramid Experience

When you visit Dahshur, you’ll find yourself surrounded by a quieter landscape compared to the bustling Giza plateau. The Black Pyramid is not open for entry due to its fragile state, but standing near it offers an atmospheric glimpse into Egypt’s Middle Kingdom past.

Nearby, you can also explore the Bent Pyramid and Red Pyramid of Sneferu, making Dahshur an incredible open-air museum of pyramid evolution.

Hawara: The Hidden Gem

The Hawara Pyramid, located near the modern town of Faiyum, feels even more off the beaten path. While much of the structure has eroded, its importance is undeniable. Exploring Hawara connects you not only with Amenemhat III but also with later Egyptian, Greek, and Roman influences in the region.

Travelers often combine a visit to Hawara with the Faiyum Oasis, a lush area filled with palm groves, birdlife, and ancient waterworks. This blend of history and natural beauty makes the trip truly rewarding.

Tips for Tourists

-

Best Time to Visit: October to April, when temperatures are cooler.

-

How to Get There: Dahshur is easily accessible as a day trip from Cairo. Hawara requires more planning, usually via tours to the Faiyum region.

-

What to Bring: Comfortable shoes, water, sun protection, and a camera for capturing the haunting beauty of the ruins.

-

Combine Attractions: Pair your visit with Giza, Saqqara, or the Faiyum sites for a complete pyramid-hopping experience.

Nearby Attractions

-

Saqqara: Home to the Step Pyramid of Djoser, a must-visit for pyramid enthusiasts.

-

Faiyum Oasis: A natural paradise with lakes, waterfalls, and birdwatching.

-

Meidum Pyramid: Another experimental pyramid worth exploring.

These sites add depth to your journey, helping you understand the full evolution of pyramid building in Egypt.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why did Amenemhat III build two pyramids?

The Black Pyramid at Dahshur suffered structural problems, prompting him to build a second, more stable pyramid at Hawara.

2. Can you enter the Black Pyramid?

No, it is closed to visitors due to instability. However, you can explore the area around it.

3. What was the Labyrinth of Hawara?

It was a massive mortuary temple attached to the Hawara Pyramid, described by ancient Greek historians as one of the greatest wonders of Egypt.

4. Are the Faiyum Mummy Portraits connected to Amenemhat III?

Not directly. They were discovered at Hawara but belong to the Roman period. They highlight the site’s long-lasting sacredness.

5. Which pyramid should tourists prioritize?

If time is short, Dahshur is more accessible from Cairo, but Hawara offers a more unique and off-the-beaten-path experience.

Conclusion

The Pyramids of Amenemhat III are more than crumbling stones in the desert; they are monuments to ambition, ingenuity, and the eternal human desire for remembrance. They may not gleam like Giza’s pyramids, but their stories are just as compelling.

For tourists, standing near these pyramids is to feel the pulse of a pharaoh’s vision that still echoes across 4,000 years. Visiting Dahshur and Hawara offers a journey into Egypt’s Middle Kingdom — a chapter of history that deserves as much admiration as the Old and New Kingdoms.

If you’re planning your trip to Egypt, don’t miss the chance to walk in the footsteps of King Amenemhat III, whose legacy of power and innovation still lingers in the desert winds.